By now you’ve probably heard of context engineering, which is the new term for setting up everything an LLM sees before it gives you a response. While some view it as a paradigm shift in how we work with LLMs, we actually think “context engineering” **is just prompt engineering done right**. If you were doing prompt engineering *well*, you’ve probably already been doing context engineering.

Here’s why.

Good prompt engineers have always known that an LLM’s output depends on everything in the context window, not just the instruction. What’s changed isn’t the practice but the packaging: “context engineering” offers a better label for what we do, which is curating, structuring, and sequencing what we send to the model, not just having a good prompt.

This isn’t just theory for us. It’s why we built Mirascope and Lilypad for managing the entire context as a single unit of code that’s traceable, versioned, and reproducible. Our goal isn’t just clean code; it’s having predictable, explainable results from a fully engineered system.

In this article, we’ll break down where the term context engineering came from, how we’ve been practicing it all along, and how you can build systems that deliver the right context to your models, with concrete examples from [Mirascope](https://github.com/mirascope/mirascope), our lightweight toolkit for building LLM applications, and [Lilypad](/docs/lilypad), our open source framework for context engineering.

## Where Context Engineering Came From

The shift to context engineering didn’t happen by accident, but came about due to the popularity of stateful, tool-using agents. These needed a way to spontaneously gather, manage, and control context across different stages of an interaction since static prompts weren’t cutting it, especially when workflows became complex and changed with every interaction.

As developers started incorporating agents and multi-turn assistants into systems, they kept running into the same kinds of failures. And these weren’t necessarily due to the limitations of the model but rather to incomplete, irrelevant, or poorly structured context.

For example, an AI coding assistant tasked with debugging a user’s Python script might begin repeating incorrect explanations or suggesting irrelevant fixes. The issue wasn’t with the model’s core reasoning ability, but rather that its context window included outdated tool outputs, redundant chat history, and missing references to earlier parts of the code. The assistant “forgot” what problem it was solving because the context it received was noisy or incomplete.

Many developers attempted to handle these failure points by focusing on techniques like Chain-of-Thought, Skeleton-of-Thought, and other strategies for improving reasoning by guiding the internal thought process through carefully structured textual cues.

While this led to improvements, it often still fell short in reliably mitigating failures in reasoning, memory retention, and tool usage in complex workflows with lots of steps.

Many times, what was happening was actually poor context (rather than poor reasoning), which suggested the need to take a system-level approach for managing the entire information environment, not just the context window and prompt.

So the challenge became not just *what* to inject into the system prompt, but *when* and *how*; context engineering emerged to solve this orchestration problem at runtime.

Here, [LLM agents](/blog/llm-agents) aren’t just model wrappers but context orchestrators that build, refine, and use context dynamically.

Context engineering basically formalizes all this into a set of evolving practices, like memory management, RAG, and tool integration. In short, it covers everything an LLM needs to operate effectively.

## Context Engineering by Another Name

At its core, context engineering reflects how LLMs actually work: models respond not just to what you say, but how you say it. Take for example two identical prompts where you tell one to respond as a poet and the other as a concise assistant. The outputs of both will differ but the extra framing is “context.”

Or imagine telling a coding agent to update a login flow to support two-factor authentication. You provide no further details in one instance, but give it specific file names and line numbers to modify in another.

Both prompts may be structurally identical, but the second provides that needed context that makes the task more reliably solvable.

Earlier, we wrote an article on [prompt engineering best practices](/blog/prompt-engineering-best-practices) and looking back, almost everything we recommended can be seen as context engineering.

For example, we advised to “Specify Exactly What You Want,” which is really about giving the model the right context around the goal. When we wrote, “Show What ‘Good’ Looks Like,” it was really about providing examples to help the model understand what we’re looking for (again, added context).

Each of these best practices isn’t just about writing a better prompt, but about shaping the information environment surrounding it so the LLM performs well. In that sense, prompt engineering has always been context engineering by another name.

## How to Do Context Engineering

### Understand What Context Means in Your Application

Context is produced by the [LLM orchestration](/blog/llm-orchestration) layer of your application (the logic that collects, structures, and sequences everything the model sees), which assembles context and sends it to the LLM. So, apart from the prompt template, “context” might include:

* **System instructions or persona**: high-level directives defining the model’s role, personality, and constraints. For example, you might tell the model, “You are a helpful legal assistant specializing in contract review.” These kinds of instructions anchor the model’s behavior across the interaction and guide how it responds.

* **User input**, which is the question or command that triggers the model to generate a response.

* **Short-term or long-term memory**. Short-term memory is like a conversation buffer that holds recent exchanges to keep the interaction coherent. Long-term memory is more persistent, storing facts, user preferences, or summaries from previous sessions. This is often kept in external storage, like a vector database, and retrieved when needed to provide continuity across interactions.

* **Retrieved knowledge** (relevant in a [RAG application](/blog/rag-application)) involves using automation to pull in up-to-date, factual information from external databases or knowledge sources to help the model ground its responses and reduce hallucinations.

* For AI agents that use tools, context likely includes **tool definitions and outputs**. The model must know what tools are available, like APIs, search functions, or databases, along with their names, descriptions, and parameters. After the model calls a tool, the output from that tool is added back into the context so the model can use it in the next reasoning step.

* In some [LLM applications](/blog/llm-applications), you’ll also want to define **structured output formats**, like JSON or XML, so the model returns data in a predictable, machine-readable form. This helps ensure the outputs can be reliably used in downstream systems.

* Some agents use an **internal scratchpad** or working memory where the model keeps its intermediate thoughts, calculations, or plans. This isn’t part of the conversation history the user sees, but it helps the model think through complex problems step by step.

Once you understand which pieces of context are needed, the next step is to develop the logic that assembles them at runtime.

### Structure and Manage Context

Designing a system that delivers complete and well-structured context to the model requires a number of things, including:

* Making sure information stays relevant to the current task or query to avoid noise that could confuse the model.

* Managing token limits to prioritize the most important pieces and compress or summarize where necessary.

* Structuring context in a logical, readable sequence so the model interprets the relationships between different pieces of information.

* Using consistent formatting for retrieved data, tool outputs, and structured inputs so the LLM can process them reliably.

When choosing a platform for context engineering, look for tools that allow you to manage context easily by structuring or centralizing what the model needs, like the prompt, memory, retrieved knowledge, and tool outputs.

An observability tool should track not just prompts and outputs, but the full picture of each LLM interaction, including input arguments, retrieval steps, tool calls, latency, and cost. This makes it easier to debug problems, measure the impact of changes, and understand how context variations influence results over time. Ideally, the framework should also make it easy to reproduce any outcome or roll back to a previous state when needed.

This is where purpose-built [LLM frameworks](/blog/llm-frameworks) make a difference. Platforms like [Mirascope](https://github.com/mirascope/mirascope) and [Lilypad](/docs/lilypad) provide out-of-the-box, pythonic abstractions for managing the context fed into the prompt.

For example, we encourage developers to structure context as a single block of code consisting of a Python function, along with decorators for the prompt template, LLM call, tracing, tools, and others.

This colocates everything that influences the LLM’s output and makes the code readable and manageable.

We typically express the prompt as a Python function and include decorators for calling and observability:

```python

import lilypad

from mirascope import llm

lilypad.configure(auto_llm=True)

@lilypad.trace(versioning="automatic") # [!code highlight]

@llm.call(provider="openai", model="gpt-4o-mini") # [!code highlight]

def answer_question(question: str) -> str: # [!code highlight]

return f"Answer this question in one word: {question}" # [!code highlight]

response = answer_question("What is the capital of France?")

print(response.content)

# > Paris

```

Here, Mirascope’s `@llm.call` decorator turns the prompt function into a call with minimal boilerplate code. `@llm.call` also provides a unified interface for working with model providers like OpenAI, Grok, Google (Gemini/Vertex), Anthropic, and many others.

It additionally [provides functionality](/docs/mirascope) for tool calling, structured outputs and schema, automatic input validation, type hints (integrated into your IDE), and more.

The `@lilypad.trace` decorator traces and versions every change automatically, capturing snapshots of modifications within the entire function closure, including changes to:

* Prompt templates

* Input arguments

* Model and provider settings

* Pre-and post-processing logic

* Tools and schema used

* Retrieval steps or embeddings

* Helper functions and in-scope classes

This treats the entire call to the LLM as a non-deterministic function taking a set of inputs (the function’s arguments) and returning a final, generated output (the function’s return value).

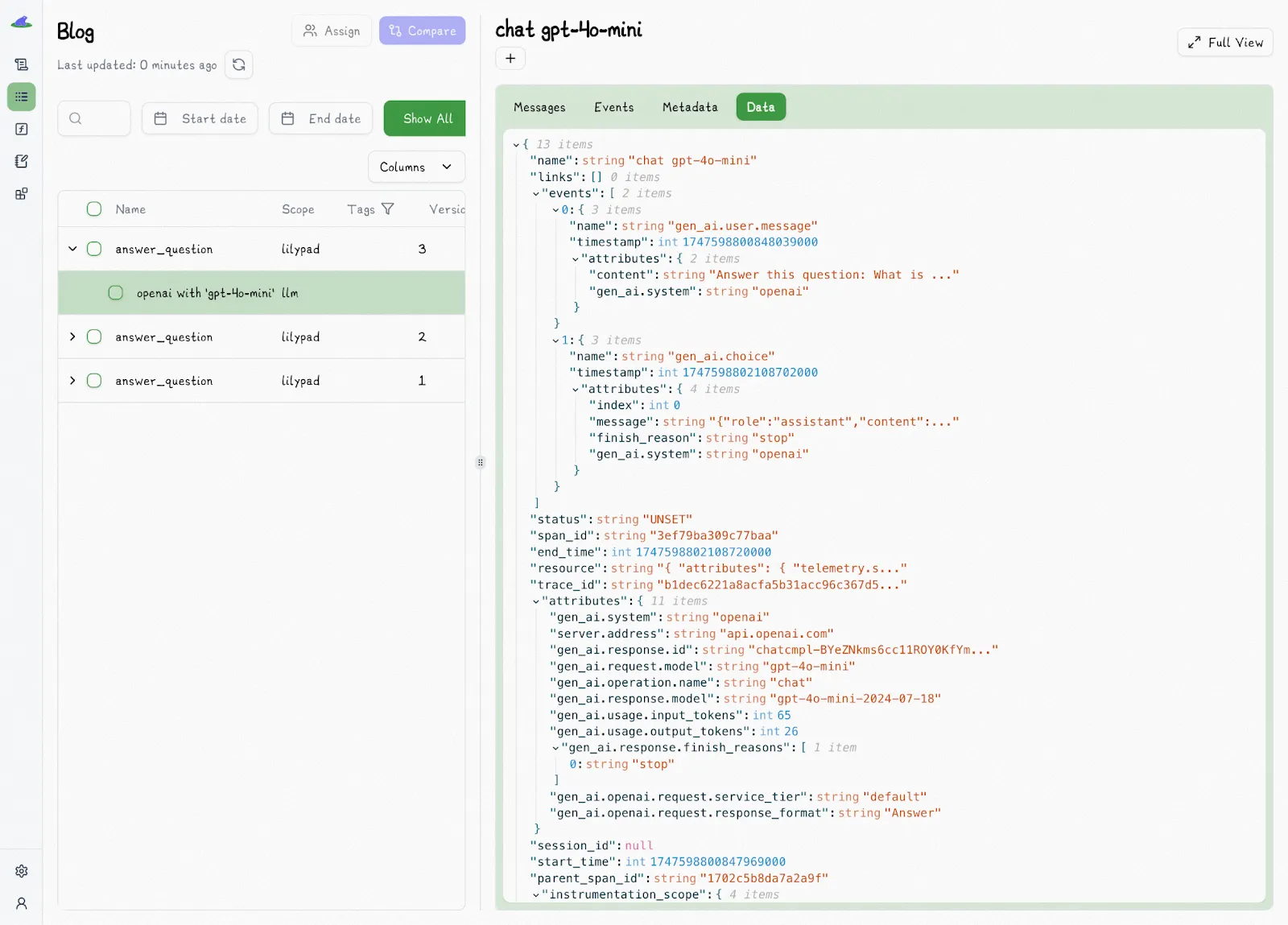

Lilyad also uses the [OpenTelemetry Gen AI spec](https://opentelemetry.io/) to instrument calls and their surrounding code, capturing metadata like costs, token usage, latency, messages, warnings, and more.

You view all this in the Lilypad UI:

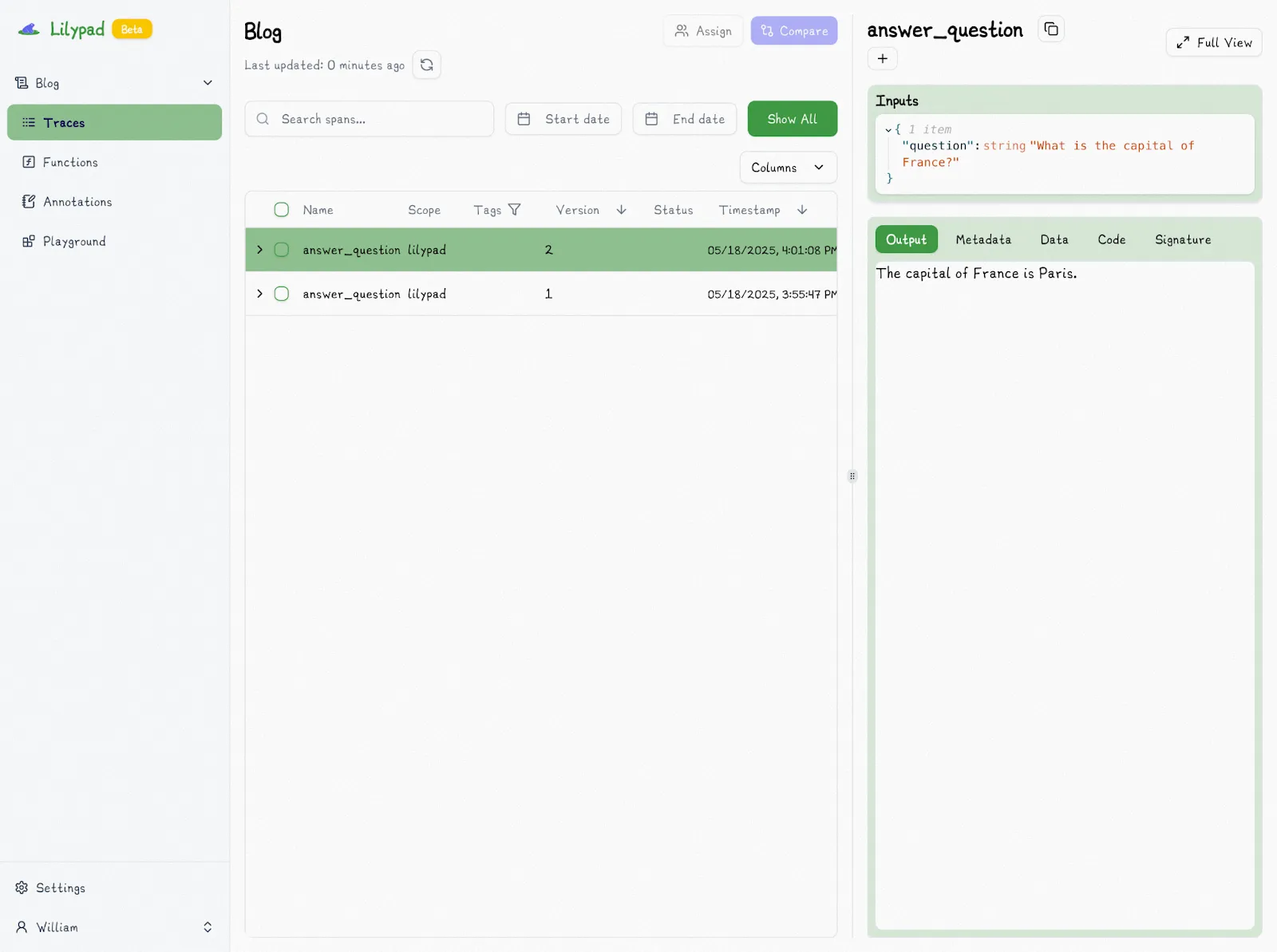

Lilypad traces both at the level of the API and at the level of each function decorated by `@lilypad.trace()`. The latter gives you a full snapshot of the entire context influencing an LLM call’s outcome, which contrasts with other tools often focusing solely on prompt changes.

The Lilypad UI also shows the outputs of every call, as well as any changes made to the prompt or its context:

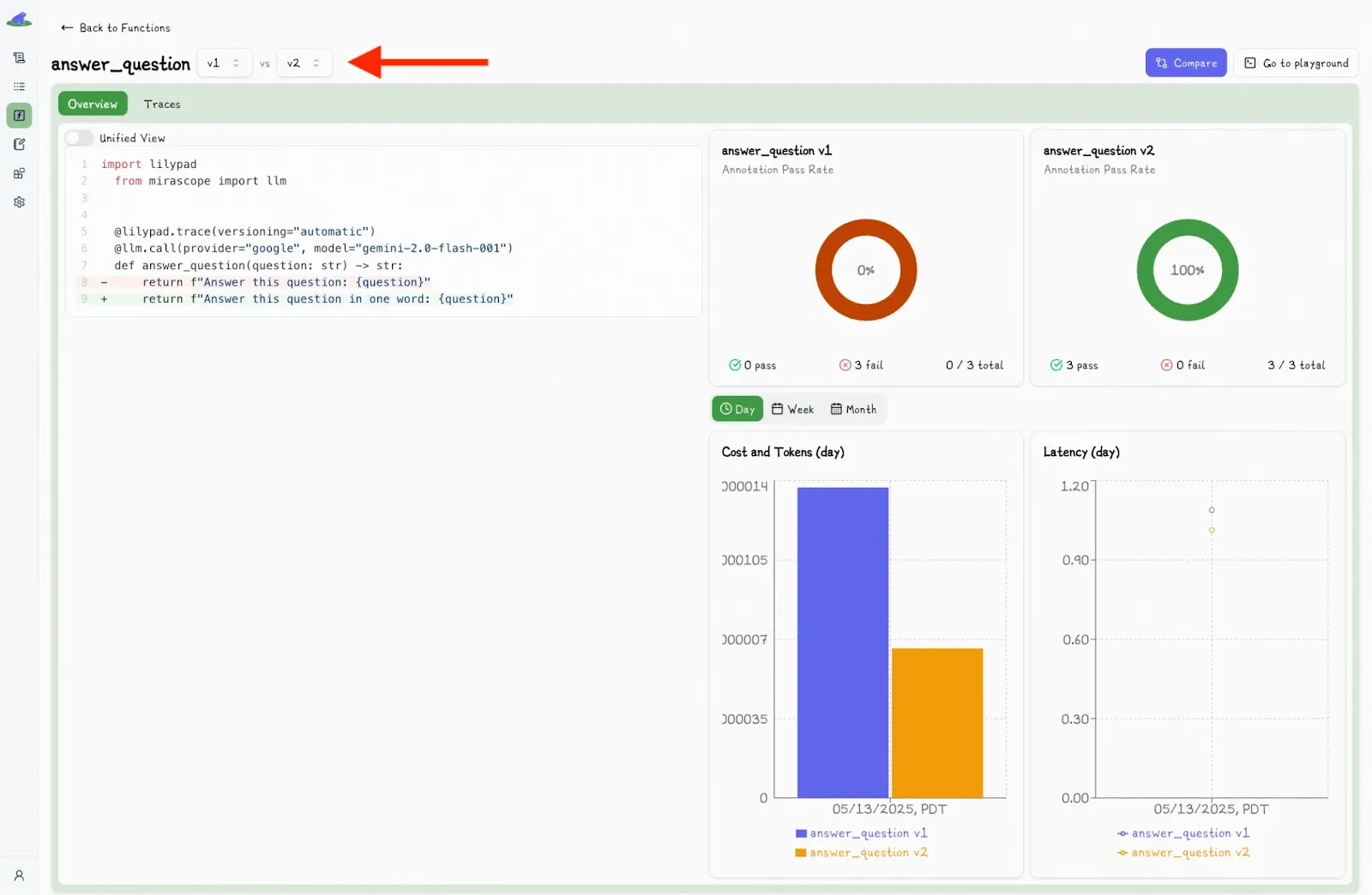

This offers a picture of the impact of any changes to the code or prompt, which you can also compare with previous calls or versions:

### Refine Model Behavior Through Collaborative Prompting

SMEs bring the domain expertise needed to shape a prompt’s framing, tone, and specificity, all of which directly influence context quality. Developers may know how to structure a system prompt technically speaking, but it’s often the domain expert who knows the right use case, language, examples, and constraints to guide the model to better outputs.

Because prompts define so much of what the model sees, letting SMEs formulate them becomes a direct lever for improving model reliability and relevance.

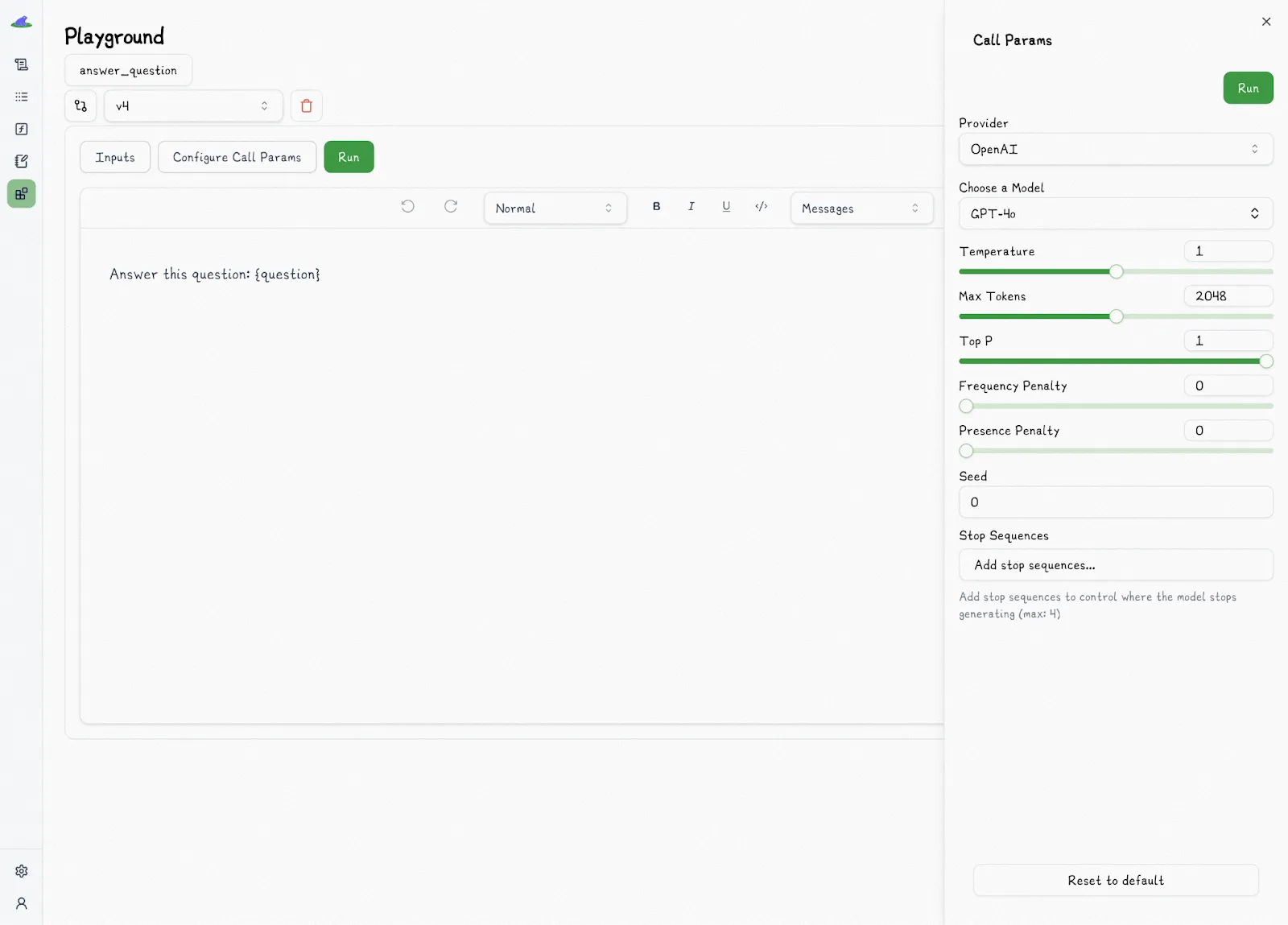

Lilypad provides a playground featuring markdown-supported prompt templates, allowing users to:

* Write, test, and iterate on prompts.

* Change call settings, like provider, model, and temperature.

* Specify prompt arguments, variables, and values based on Lilypad’s type-safe function signatures.

Prompts are attached to a versioned function, and every time it runs, it’s automatically versioned and traced against that function. SMEs can develop and run code independently of developers, who can access prompts and context via methods like `.version` that return type-safe signatures matching the expected arguments for that version:

```python

response = answer_question.version(1)("What is the capital of France?")

```

Other systems treat prompts as standalone assets managed separately from the application code, which developers then have to pull downstream. Lilypad takes a different approach by versioning prompts as part of the code itself, ensuring that what runs in the playground is the same type-safe code developers run downstream in production, eliminating the brittleness of separating prompts from the rest of the system.

### Improve Context Quality Through Evaluation

Without evaluation, it’s hard to know whether the issue lies in the prompt or with bad or good context, like the retrieved knowledge, or the way information is structured for the model.

Systematically evaluating outputs creates a feedback loop that guides how you refine the inputs feeding into the model. Over time, this helps teams track which context strategies improve reliability and which ones introduce noise or confusion. Ultimately, evals aren’t just about judging the model’s performance in isolation; they’re about debugging and improving the entire information environment that surrounds it.

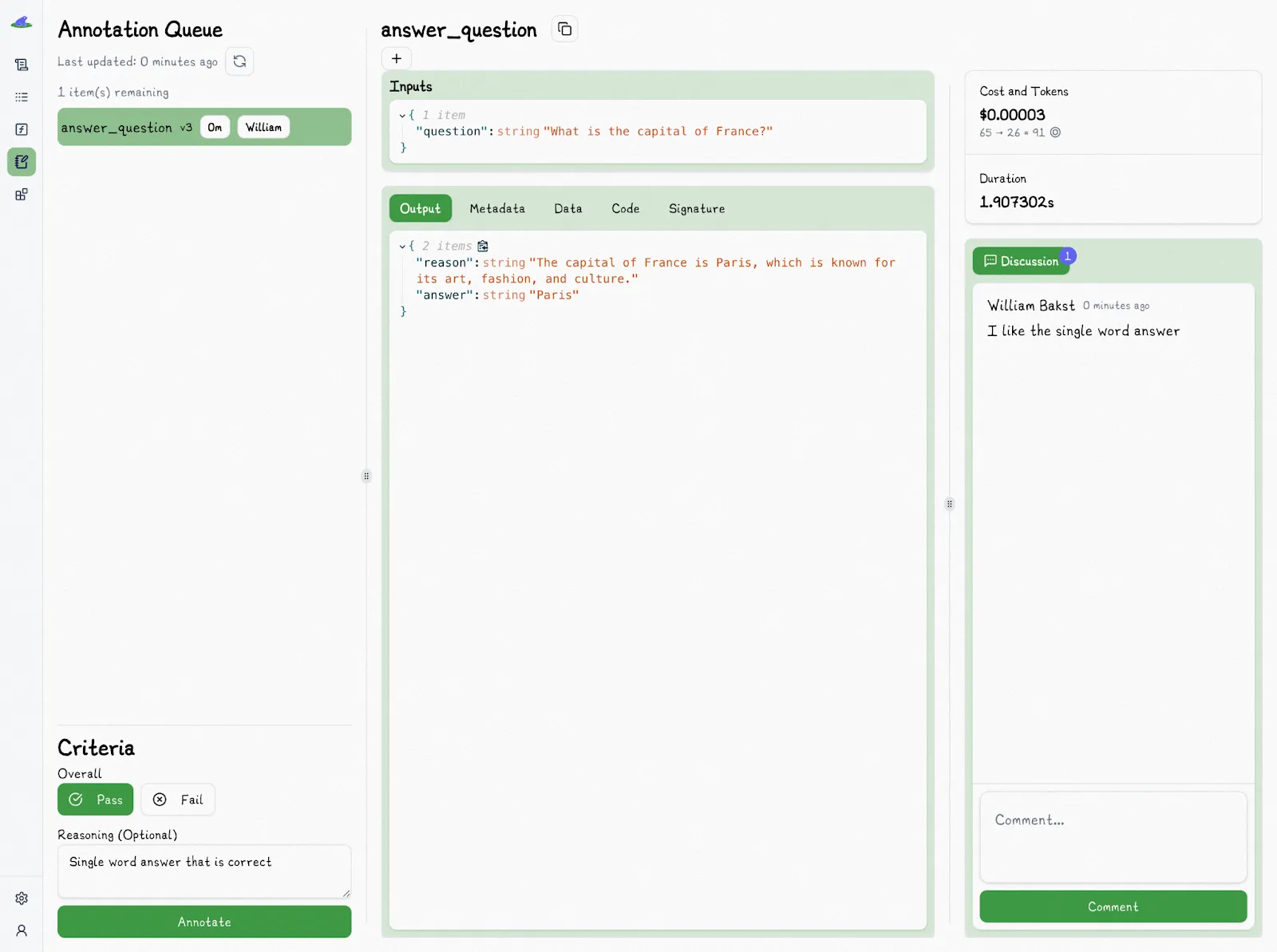

Lilypad also provides features letting you select an output or trace to annotate with “Pass” or “Fail” to quickly capture whether a particular context setup led to a successful result. You can also add an optional reason for your decision, which helps teams pinpoint patterns in failures and understand where context adjustments are needed:

We find that in real-world evaluations, you’re often optimizing just for correctness and so a simple pass/fail assessment is a good-enough metric to measure success, rather than a complex scoring system.

Even granular scoring systems, like rating outputs on a scale from 1 to 5, can be difficult to apply consistently. It’s often unclear what precisely separates, say, a “4” from a “5,” and even with defined criteria, such ratings tend to remain subjective and unreliable.

Lilypad also allows team members to collaborate on evals by providing discussion panels and assigning particular tasks to other users.

Our [documentation](/docs/lilypad/evaluation/annotations) provides more details on these and other features that make evaluation workflows more systematic and closer to software development practices.

## Build Better AI Systems with Context Engineering

If you’re ready to move beyond basic prompting, Lilypad and Mirascope offer everything you need to structure and control your model’s context for scalable [LLM integration](/blog/llm-integration). With abstractions for prompt templates, memory, retrieval, tool integration, and observability, they give you the scaffolding to build production-grade agentic systems.

Want to learn more? You can find more Lilypad code samples on both our [documentation site](/docs/lilypad) and [GitHub](https://github.com/mirascope/lilypad). Lilypad also offers first-class support for [Mirascope](https://github.com/mirascope/mirascope), our lightweight toolkit for building AI agents.

What is Context Engineering? (And Why It’s Really Just Prompt Engineering Done Right)

2025-08-06 · 5 min read · By William Bakst